Exploring the Open Data Barometer: Latin American Edition

Last week, ILDA launched a 2020 Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) edition of the Open Data Barometer (ODB), shining a light on how open data policies and practices have evolved in the region since the last measurements in 2016 (most countries in the region) and 2017 (a selected few for the ODB ‘Leaders Edition’).

Both the development of the Global Data Barometer, and the regional ODB that ILDA has run in LAC, respond to demand from governments and other stakeholders for ongoing data to inform policy design, benchmark progress, and support comparative learning. In this post, we reflect on some of the findings from this latest regional assessment of open data readiness, implementation, and impact—and some of the questions they raise that we’ll be seeking to answer in the new Global Data Barometer study.

Improved availability, but absent impacts?

As the executive summary reports: “Since the last measurement, four years ago, Latin American and Caribbean countries have made progress in making public data more open and accessible, but these advances have not been transformative.”

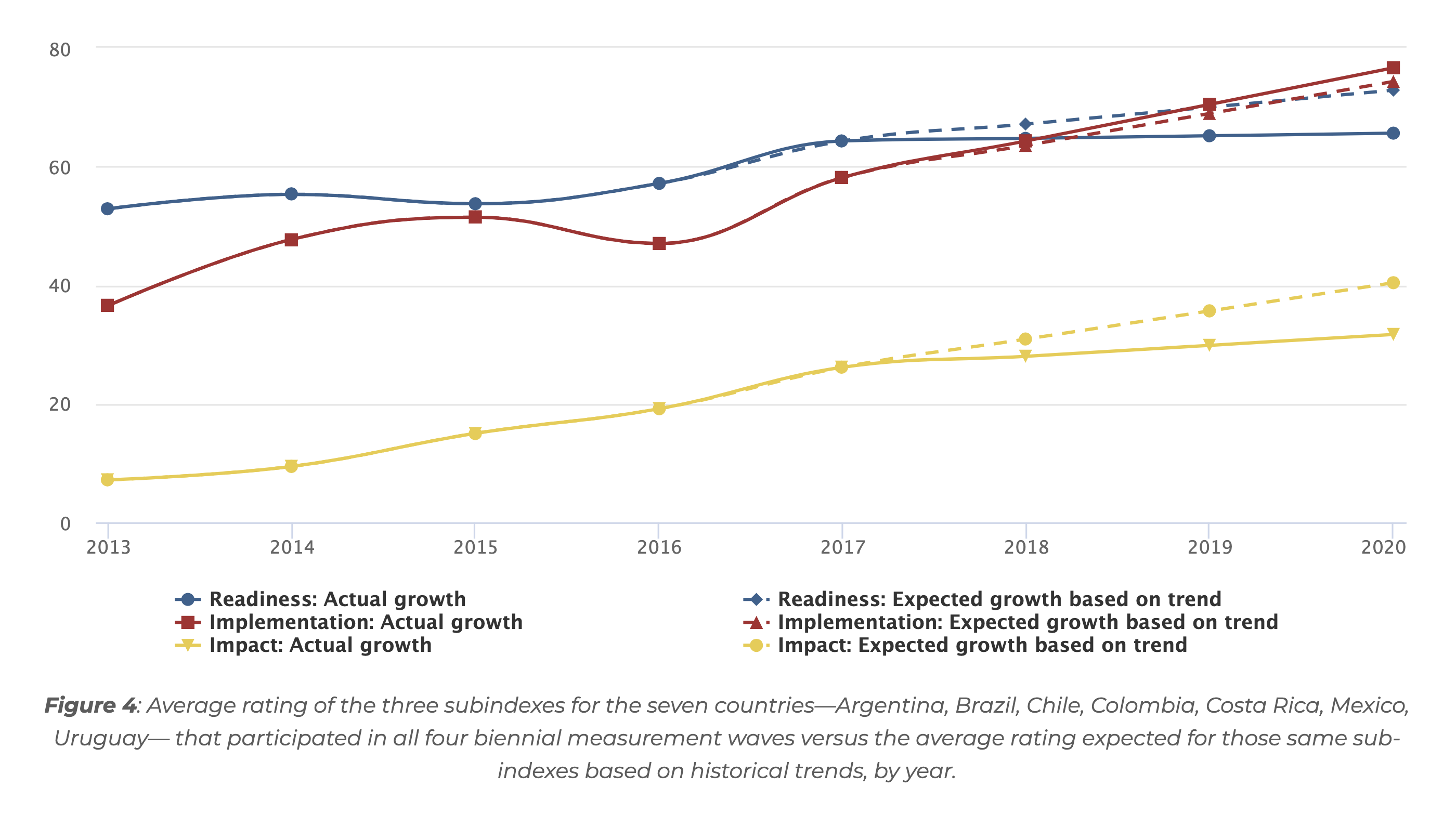

Trends in ODB sub-index scores show that whilst the publication practices for a selected set of open datasets have improved faster than the historical trend (the implementation sub-index), indicators from the readiness sub-index—which measures how prepared countries are in terms of their policy and capability to secure impact from open data—have more or less flat-lined. Unsurprisingly, this lack of progress on the wider enabling environment for open data appears to also be reflected in the very limited growth in impact scores.

Digging into the report’s qualitative analysis, we can see that the overall flat-lined readiness scores hide substantial volatility in country policies and capability: political transitions and other factors have led to earlier open data policies being abandoned or de-prioritised, or to responsibility for driving open data activities being shifted to different teams.

What we can’t see from the methodology of the Barometer (both in this and previous editions), is whether this reflects a shift to focus on other areas of the data landscape (e.g., big data or data analytics, as Eaves, McGuire, and Carson’s chapter in The State of Open Data suggests they might), or a general failure to develop and sustain coherent (open) data strategies over time. The structure and indicators in the ODB also don’t allow us to disentangle the policy dimensions of readiness from the capability dimensions of readiness. An environment that enables open data may require both the governance frameworks for trustworthy and reliable flows of data, and the capacity in government and civil society to sustain supply and demand for that data.

One of the great assets of the ODB approach—one we will replicate in the GDB—is the publication of all the underlying responses collected through the expert survey. This allows us to look at the evidence that researchers present in response to impact questions.

ODB impact questions take the form “To what extent has open data had a noticeable impact on [ X ]? where X is an anticipated outcome of open data activities such as ’increasing government efficiency and effectiveness’, or ‘environmental sustainability’, amongst others. Looking at this evidence from the LAC ODB highlights the continued challenges of operationalising this form of impact question: comparisons between countries can be affected both by actual impacts and by the degree to which there are publications or resources that attribute certain outcomes to open data.

Such challenges are why we’re exploring a new model of use and impact question in the GDB, looking for specific use cases of data, rather than broad societal impacts. We hypothesise that, by looking for specific use cases (such as, for example, use of procurement data for accountability efforts), we may be able to see more clearly the connections between data availability, use, and impact—and to better track which impacts are one-offs, and which are sustained and become embedded in governance systems.

Capacity, Inclusion, Partnership & Quality

Since the Open Data Barometer methodology was drafted in 2012, there has been growing focus in the open data field on gender equity, on inclusion, and on the diverse topics and spaces where open data can be put to use. The LAC Barometer confronts the limitations of the 2012 methods in writing:

“Although this methodology is very useful for understanding the state of data openness in a given country and comparing data openness across countries, it covers only a few topics and does so in limited depth. While this restricted scope helps strengthen the validity of the cross-country comparison, in the context of an increasingly diverse agenda, the methodological limits may cause us to miss many nuances and variants”

“Furthermore, one of the methodological limitations of the current study is the omission of measures related to inclusion and diversity; the low levels of social impact nonetheless suggest how little progress has been made toward the goal of including marginalized groups”

However, building on the qualitative insights as well as indicator evidence, the LAC Barometer draws out four key recommendations for the future:

- Governments must consistently and sustainably invest in teams that guide and implement open data policies at all levels of government.

- Governments should holistically consider the different aspects of the production and use of data from the public and private sectors, including regulatory aspects regarding privacy, use of data for the common good and emerging technologies and should focus on including the most vulnerable people in society.

- Governments must redouble their efforts to include the private sector and civil society in the open data ecosystem in order to advance the agenda and generate more and better uses of data to produce benefits for various groups in society.

- Governments should improve the quality of their data, taking special care to consider gender dimensions as well as other relevant variables, so that data include all people in their societies.

All of these track well with the direction of travel in the Global Data Barometer (and the findings of The State of Open Data). In the first edition of the GDB in 2021, we will be taking in the wider governance environment around data production and management, seeking to better understand the interaction between different sectors of the economy in gathering, providing, and using data, and asking questions that dig into issues of data quality. We will also be placing strong emphasis on questions of inclusion, diversity and gender equity, and finding approaches to allow researchers to highlight the unique aspects of their national data ecosystems, as well as the comparable components.

In doing so, we don’t move away from seeking to understand open data, but we set open data in its wider context. As the LAC report concludes “In the digital age, sustaining democracy and an informed citizenry […] depends on open data.” We need continued reflection and knowledge exchange to make sure the potential of open data is further realised.

A note on two studies. Unsurprisingly, there can sometimes be confusion between the ODB and GDB.

The Global Data Barometer is a new initiative: one that builds on learning from the Open Data Barometer and aims to maintain some continuity of indicators to support research and analysis that would benefit from a reasonably consistent time series.

The Open Data Barometer was a project of the World Web Foundation. The first two editions were designed and managed by GDB Project Director Tim Davies, and then taken forward by other members of the Web Foundation team (particularly under the leadership of Jose Alonso and Carlos Iglesias). The last full edition of the Open Data Barometer took place in 2016, with a smaller ‘leaders edition’ in 2017. Since 2018, the Web Foundation has allowed and supported other organisations to independently carry out regional Barometer-based studies, using the same methodology and survey tools. Regional studies have been carried out for Africa (2018) and Latin America and the Caribbean (2020), and a number of organisations have based other assessments on the ODB methodology (which is available for anyone to use under an open license).

The Global Data Barometer is an independent project, organisationally based within ILDA, supported by the Data for Development network, and run through a broad partnership of organisations. The Web Foundation is not currently a Global Data Barometer partner and is not involved in its development.

The first edition of the Global Data Barometer, with its broader focus on data governance, capability, availability, and use for the public good, will be released in 2021. We are not aware of any plans for further editions of the ODB.