A Global Data Barometer Progress Update

Now that the full Global Data Barometer project has been up and running for two months, I wanted to share some thoughts about where we have come from, where we have got to, and where we’re headed in the coming months.

Looking back: from idea to project

The idea for the Global Data Barometer emerged in conversations at the Open Government Partnership Summit in May 2019.

In reviewing ten years of open data for the State of Open Data book, it had become clear that, to remain relevant in the decade ahead, open data needed to be situated within the landscape of contemporary data policy. The Open Data Barometer study—Global Data Barometer’s predecessor project, which ran from 2012–2017—told us a lot about country-level open data policies and practices. What we lacked, though, was a clear picture of how new configurations of data governance, capability, availability, and use were shaping up in different countries. And we lacked, too, a clear picture of data practice sector by sector.

The State of Open Data moved us in that direction, bringing together qualitative insights and stories from sixteen different sectors and communities and on seven cross-cutting issues. But still, when it comes to questions like, How many countries have a legal framework for provision of reliable company data? or, Which countries are making connections between their open data and AI strategies, and how? or, To what extent is open data available on the performance of Right to Information regimes? we have few comprehensive sources to turn to.

That last question came from the team working on the Open Government Partnership’s Global Report, which drew on a variety of sources to identify the connections between data and open government—but which also identified a number of critical data gaps.

All this had us wondering: Could we reboot the research mode of the Open Data Barometer (ODB) to create a new study? A study that would:

- Provide an updated, comparative assessment of countries’ (open) data policies and practices in a way that reflects the contemporary recognition that privacy and data governance concerns must be weighed alongside promotion of data reuse;

- Meet the data needs of sectoral initiatives and researchers, maximising the value from primary research by considering how the data from each indicator we cover might be used and reused;

- Contribute to global discourse around data by addressing the underrepresentation of evidence from low- and middle-income countries in the creation of data policies and practices and building research capacity across different regions;

- Provide an ODB-compatible time series to support the growing collection of papers carrying out longitudinal analysis of correlations between data availability and social, political, or economic outcomes.

With support from IDRC, we began consulting with different stakeholders to understand what they might want from a study like this. In January this year, we convened many of these stakeholders for a design workshop focussed on how best to structure both the GDB study itself and the partnerships to deliver it.

The result was twofold: a refined research framework built around four components: governance, capability, availability, and use & impact, and a funding proposal to pilot the Barometer in 2020–2021. With seed funding secured and ILDA kindly acting as the Barometer’s organisational home, we hired a team—and then in July kicked off full development.

Development phase: growing, scoping, learning, testing

Building a new team and developing new project partnerships across multiple time zones and continents during a pandemic and whilst a global recession looms has its challenges. I’m pleased to say that everyone has hit the ground running. Two months in, we’ve already begun filling in many of the details for how we’ll meet the four goals above; updates on five of the areas on which we’ve been working follow.

1. Refining GDB core concepts and the overall study framework.

Whilst the ODB measured open data alone, the GDB examines whether data is being managed at the appropriate points of the data spectrum. To capture this, we’ve been developing our operational definition of ‘data for the public good’, set out here:

Data is a source of power. It can be exploited for private gain, and used to limit freedom, or it can be deployed and governed for the public good: a resource for tackling health, social and environmental challenges, enabling collaboration, driving innovation and improving accountability.

What constitutes the public good can ultimately only be determined through open public debate: and different ‘publics’ may have different priorities at different times. We draw on established global principles, and in particular on the Sustainable Development Goals, the international human rights framework to give content to the idea of the public good used within the Global Data Barometer.

Ensuring that data is a resource for the public good involves a variety of interventions, depending both on the data in question, and the wider context. In some cases, it involves robust governance and control of data, so that risks of data abuse are minimised. In other cases, it involves promoting and supporting data re-use, to maximise the social value generated from data. In others again, it requires capacity building to equip diverse actors to work with data. In many cases, it involves all of these.

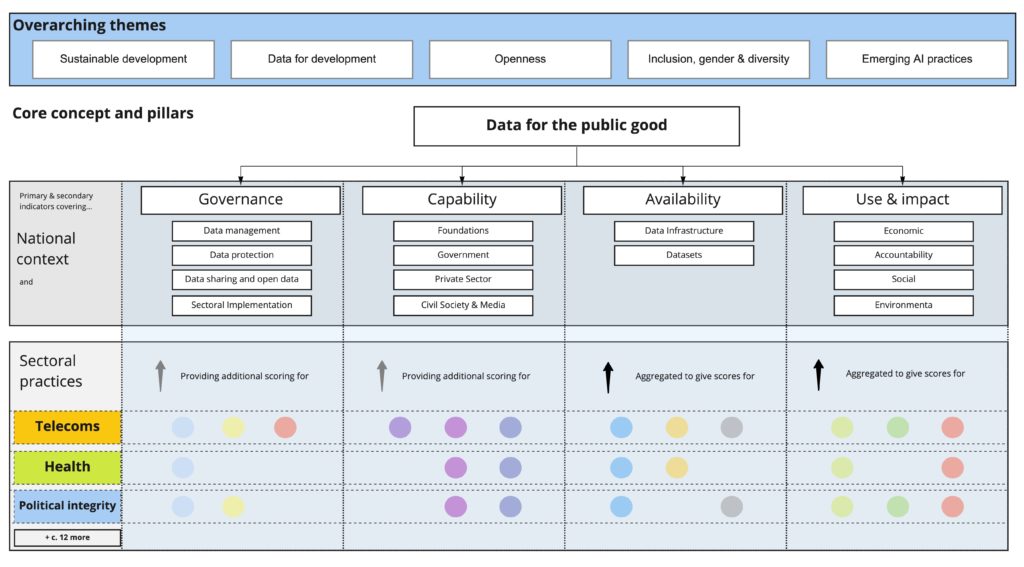

To show how different GDB components contribute to data for the public good, we’ve put together a first draft of the overall study structure, shown below.

This gives us a framework for designing individual metrics, either by creating our own survey questions or by using secondary data sources that will support comparative evaluation of countries’ strengths and weaknesses.

2. Developing thematic modules and thematic partnerships.

We’re aiming for the first edition of the GDB to include at least ten thematic modules (hopefully more), with the plan to expand upon these in future editions. Our thematic modules look at data in context; this allows us to make connections between the regulation of data, data infrastructure, and data use. It also makes it possible for us to ground our assessment of data for the public good in high-priority use cases that draw on data from a range of sectors and stakeholders.

Over the last two months we’ve been talking with many different organisations to create a shortlist of themes for the first edition of the Global Data Barometer to cover, scoping out each theme’s particular focus. For a number of themes, we’ll be taking a lead from the new Data for Development (D4D) programme, which will explore opportunity spaces for improved data practices around health and pandemic response, education, food security, and migration amongst other areas. For other themes, we’ve been establishing partnerships with sectoral specialists who can both inform indicator design and make concrete use of the data that results.

Our first pilots, focussed on Political Integrity (in partnership with the OGP and Transparency International), and Land (in partnership with Land Portal), have shown us the value of taking an iterative approach to scoping indicators—going back and forth between published literature and policy agendas, draft indicators, and examples of data and policy. We’ll soon be moving these early modules into the next phases: expert workshops, pilot testing, and open review, with the aim of making sure every indicator both reflects global norms and is sensitive to different local contexts.

3. Building regional partnerships to shape study design, manage data collection, and lead dissemination.

Regional hubs are central to the way we want the GDB to be delivered, as Veronica describes here. We’ve been building our regional hub network for the Global South on the existing OD4D partnership, whilst issuing a call for partners who can join us to establish hubs in other regions.

We’ll be announcing the organisations that form the regional hub network soon, and we’re keen to connect these hubs with potential supporters who can amplify their work. We’re committed to working with our partners to create a strong community of practice, where researchers don’t just input data into the GDB, but collaborate in its analysis and lead dissemination.

4. Refining our indicator design and survey model.

As the GDB expert survey could generate up to 1000 individual data points for each country covered, this is a fantastic opportunity to gather rich qualitative and quantitative data. To make the most of this opportunity, we’ve been testing various patterns for survey questions and have moved from the open 0–10 scales used in the ODB to a checklist-driven framework that will both help guide researchers and provide additional structured responses to support cross-country learning and comparison. (You can read more about GDB indicator design in our growing Frequently Asked Questions.)

As we increase the scale of the GDB survey, we’re trying to reduce the time researchers need to locate sources. So we’re practicing what we preach in terms of data reuse—for example, by looking at how we can bring in existing data and focussing questions primarily on annotating existing collections of laws or datasets, rather than asking researchers to locate information from scratch. As part of this endeavour, we’ve been speaking with government representatives and doing design work to make the government and civil society evidence-collection phase of the GDB as streamlined as possible.

Through engagement with regional hubs, we’ve explored possible approaches to a multilingual GDB survey, reviewing best practices for expert survey work across languages. We’ve sketched out an approach to make the survey handbook available in French with robust, conceptually accurate translations that we hope to test out before the end of the year.

Lastly, we’ve been updating the survey tool we’ll be using for data collection, removing restrictions that meant it could only run in Google Chrome and adding a resource manager so that researchers have easier ways to upload supporting evidence.

5. Communications, funding plans, and community building

We’ve been developing a communications plan for the GDB that reflects both the next three phases of the work—study design (where we’re at right now); researcher recruitment and fieldwork; and analysis and dissemination—and our current capacity. We’ve got design work underway for an updated website and report templates, so that we can start thinking early about how to present and visualise the study’s results. And we’ve been looking at the wider context we’re working in, including alignment between the GDB and the upcoming World Development Report.

We’re also looking to the future. Realising the full value of the GDB requires being able to collect longitudinal data—which means bringing together partners to secure regular data collection over the next decade. This requires an ambitious fundraising strategy, so we’ve been investigating how to engage a community of donors (working closely with the emerging D4D programme) and exploring models for organisations and firms to sponsor particular aspects of the GDBs work by theme, region, or report.

Looking ahead

The last two months have shown us that getting our partnerships, methodology, and indicator design right is going to take a few months longer than our original timeline, which anticipated fieldwork starting early in the new year. We’re currently working up a revised schedule that still has us publishing results by mid to late 2021, but which will give us a few extra months early next year to consult on final indicator design and develop resources for researchers.

In the next few months we’ll be doing more detailed scoping work on a large number of the Barometer’s thematic modules, in conversation with existing and potential partners. (If your organisation is interested in exploring a partnership with GDB, please contact veronica@globaldatabarometer.org.) Before the end of the year, we plan to share open drafts of these modules for public comment—so watch this space!